Their character were all 5-6 level, but all of our characters were higher and in the middle of the Slave Lords series. They had been over before and we had a lot of fun then. Because of the difficulty of obtaining these gamemasters they tend to have gone out of fashion at conventions down here in Oz, being replaced by non-competitive game sessions.This past weekend an old grade-school/highschool friend was in town with his kids so we played some D&D5. They're lots of fun (both to be in and to run ), although you generally need an available pool of experienced gamemasters to call on to be able to run a tournament. Even with all the gamemasters having been put through the module by the designer and extensive working notes, every gamemaster has a noticable different style. The interesting thing is that gamemaster styles are the bigger influence. There are groups that combine the two approaches (and usually win thereby), but they are actually exceedingly rare in my experience. Both styles work and are fun, and if the scoring system has been set up properly both styles are competitive. The other type are those that enjoy accumulating bonus points. The first are the characters who attempt to be uber competent and race to the objective as a smoothly working machine of dungeon plundering. After all, having fun is also an objective of playing the game. Bonus points for role-playing, overcoming obstacles with style and panache, and making the gamemaster laugh (or cry) are usually awarded.

Most tournament games I've run/been in, tend to have a fixed objective which they must reach before the end of the session, with success being measured by progress towards that objective. If I take this up at some point, I'll be sure to make some posts about it. Still, as a historical exercise, it might be worth a try. I will also admit to some trepidation, since, much as I love the very focused approach these modules possess, it's probably a lot more focused than my games ever were (or are).

Never having participated in tournaments back in the day - and, even now, the whole concept of it strikes me as odd - I will admit to some curiosity about the entire undertaking.

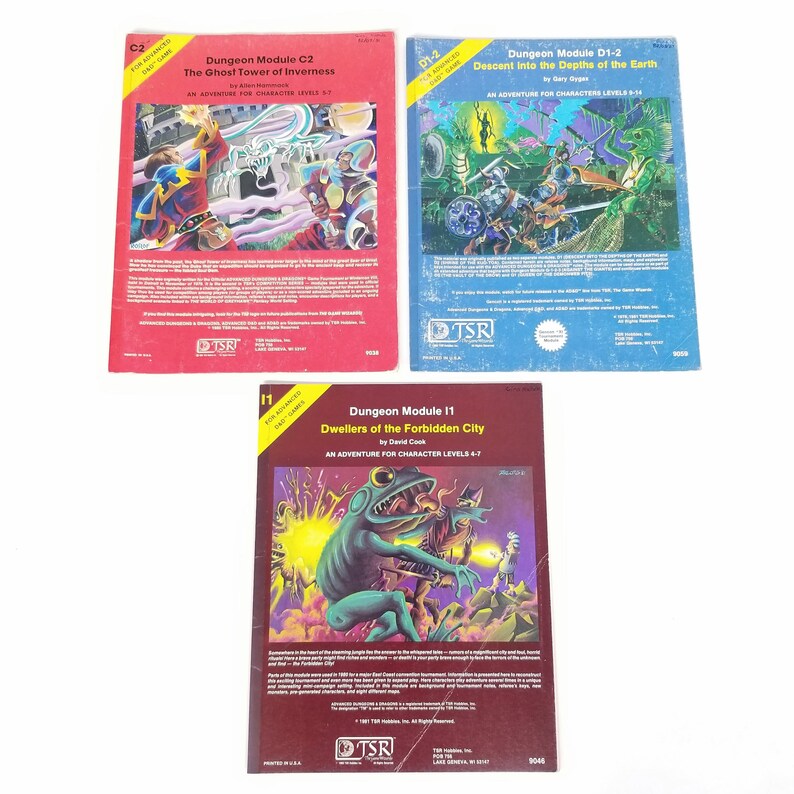

The Ghost Tower of Inverness might be fun to run as a tournament-style module someday, since it includes both pregenerated characters but also a scoring sheet. Indeed, I always felt that dungeons should include lots of really fiendish traps I simply wished I was better at overcoming them myself! As I noted yesterday, this style of play appeals to me a great deal more now than it did when I was younger, although, even then, my qualms about it had more to do with my own mental inadequacies than with any absolute dislike of the format. The Ghost Tower is a big puzzle, a brain teaser that tests the quick thinking and logic of the players. There's very little rhyme or reason to the way the place is constructed except that the challenges it presents were deemed "fun." I have to admit that they are fun. The Ghost Tower itself is something of a "funhouse" dungeon. And of course the module's MacGuffin, the Soul Gem, is itself a death trap for the unwary - a classic move that many players of a certain vintage will remember all too well. There's the chess room, the reverse gravity area, the temporal stasis room, and many more. But it's the tricks and traps that really stand out nearly 30 years later. That's because it's filled with a wide variety of ingenious - and deadly - tricks and traps, in addition to more than a few monsters. Written by Allan Hammack, it's a very difficult adventure, one that my players came to loathe when I ran it back in the day. There's definitely a lot of truth to this perspective, but we should all bear in mind that a great many TSR modules were in fact clearly identified as having their origins in tournament play and indeed made no effort to disguise this fact.ġ980's The Ghost Tower of Inverness is a good example of a tournament adventure turned into a published module. That is, the module format is largely artificial and gives a somewhat false impression about early adventure design. It's becoming accepted wisdom in old school circles that what we think of as an "adventure module" says more about the exigencies of tournament play than the way referees constructed scenarios for use in their home campaigns at that time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)